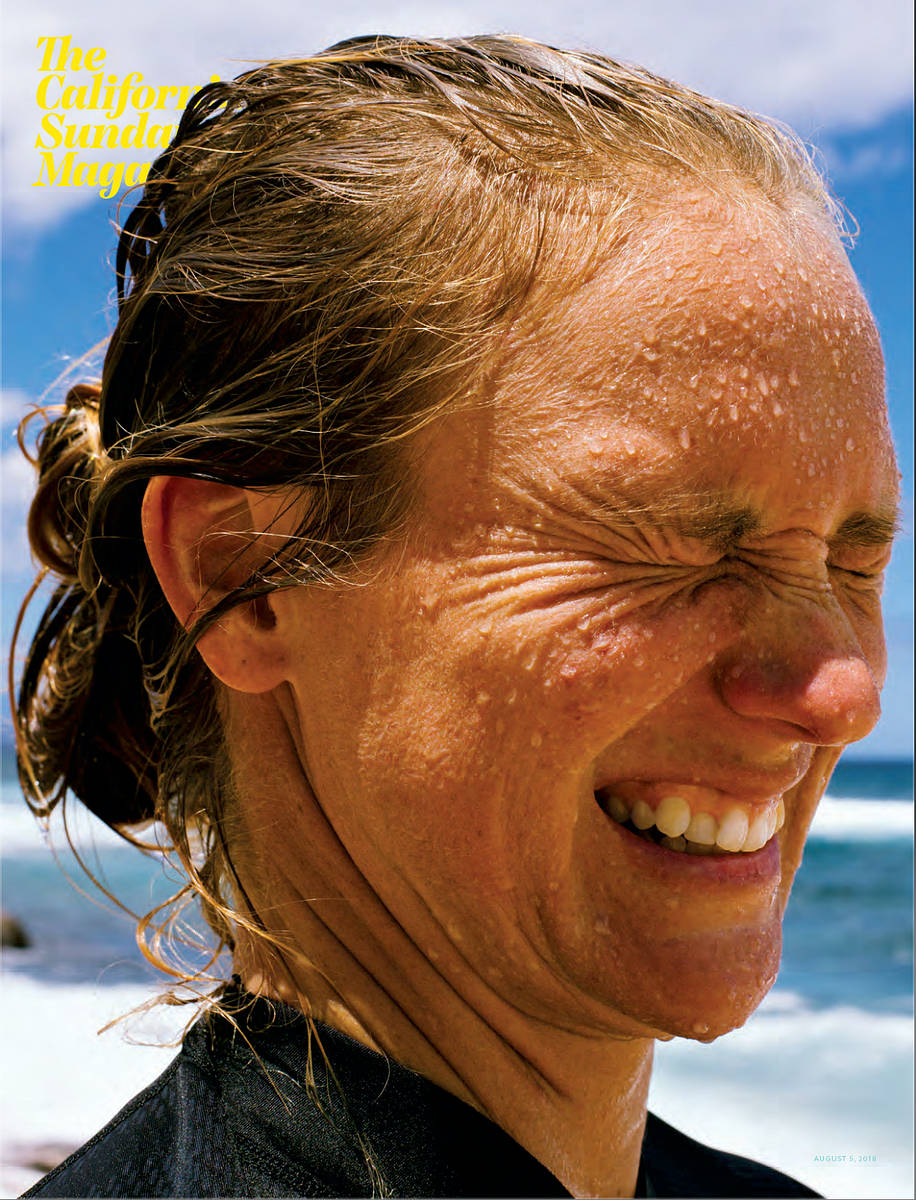

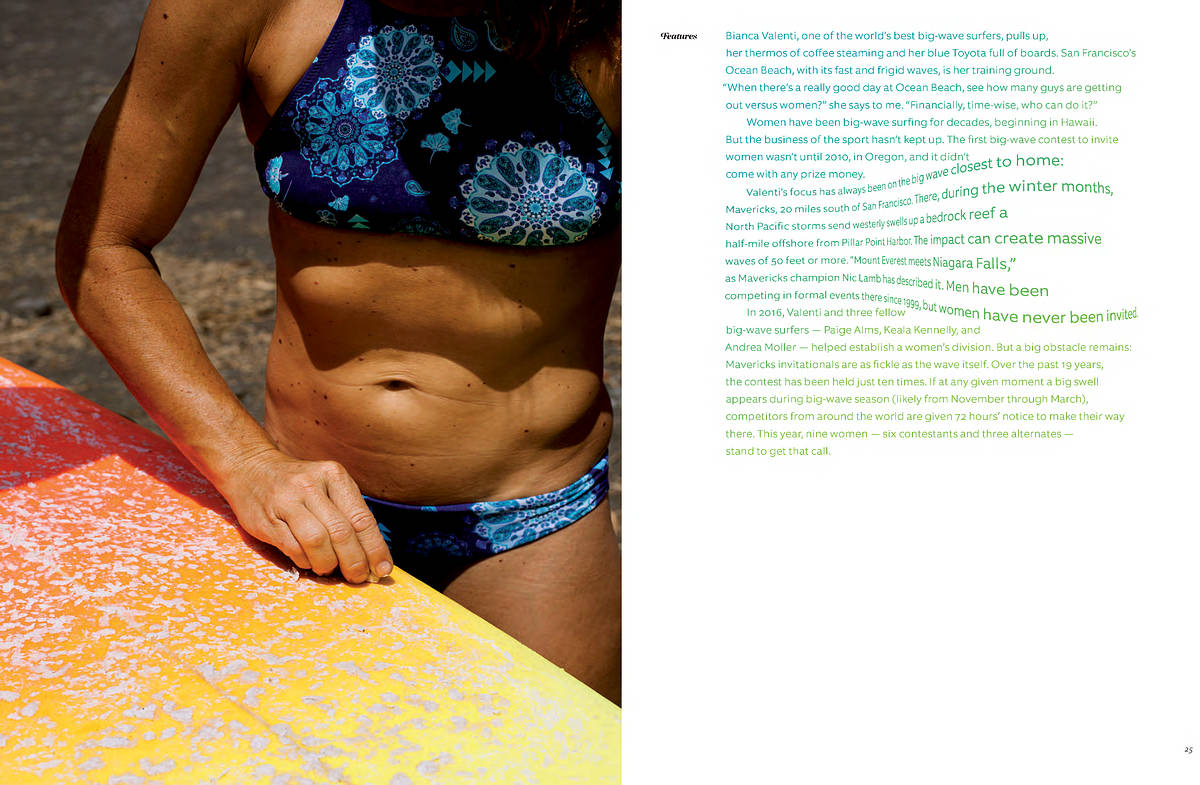

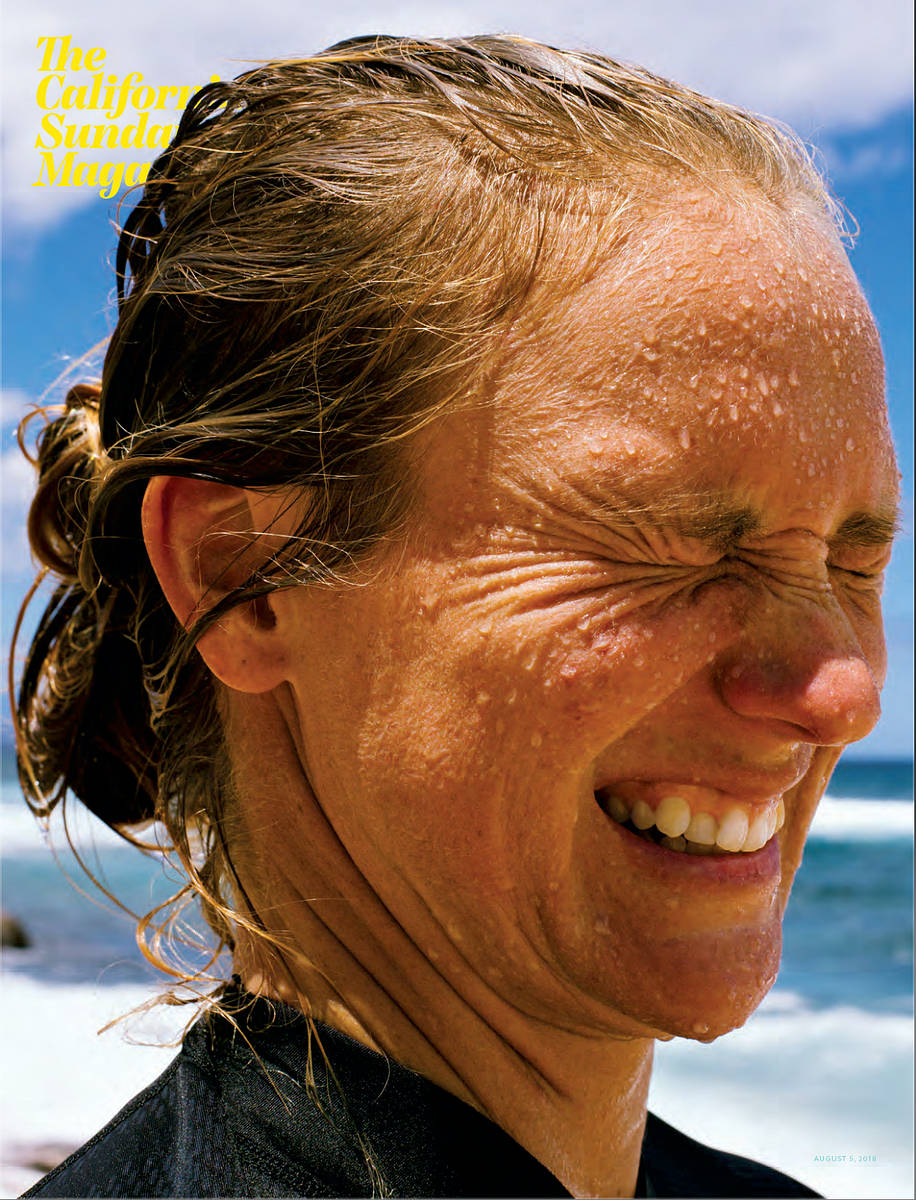

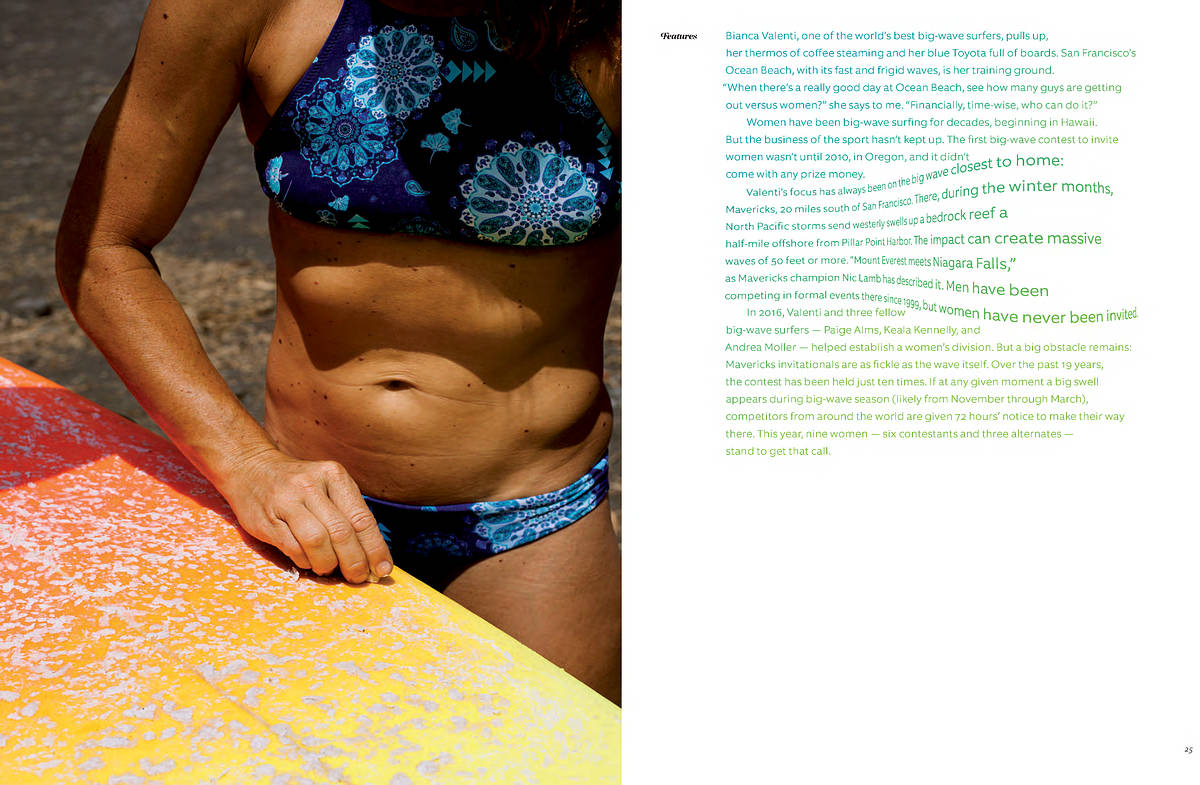

Bianca Valenti, one of the world’s best big-wave surfers, pulls up, her thermos of coffee steaming and her blue Toyota full of boards. San Francisco’s Ocean Beach, with its fast and frigid waves, is her training ground. “When there’s a really good day at Ocean Beach, see how many guys are getting out versus women?” she says to me. “Financially, time-wise, who can do it?”

Women have been big-wave surfing for decades, beginning in Hawaii. But the business of the sport hasn’t kept up. The first big-wave contest to invite women wasn’t until 2010, in Oregon, and it didn’t come with any prize money.

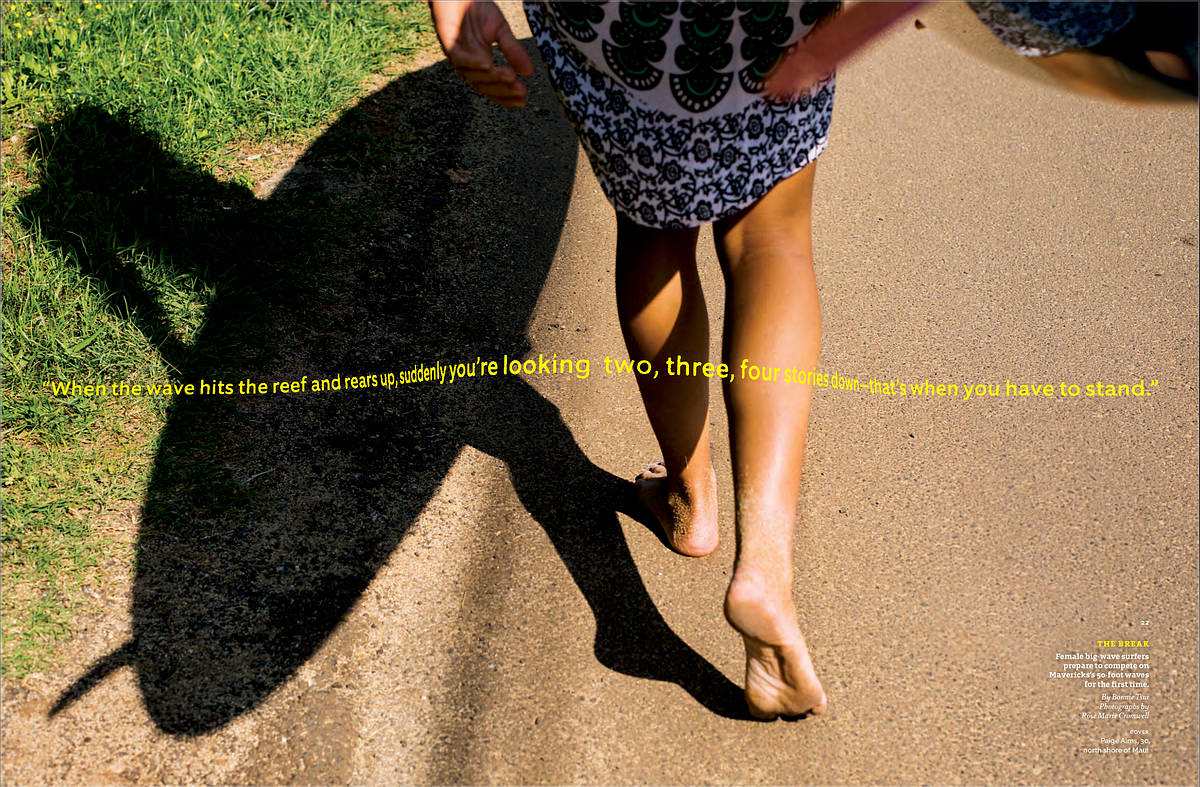

Valenti’s focus has always been on the big wave closest to home: Mavericks, 20 miles south of San Francisco. There, during the winter months, North Pacific storms send westerly swells up a bedrock reef a half-mile offshore from Pillar Point Harbor. The contact can create massive waves of 50 feet or more. “Mount Everest meets Niagara Falls,” as Mavericks champion Nic Lamb has described it. Men have been competing in formal events there since 1999, but women have never been invited.

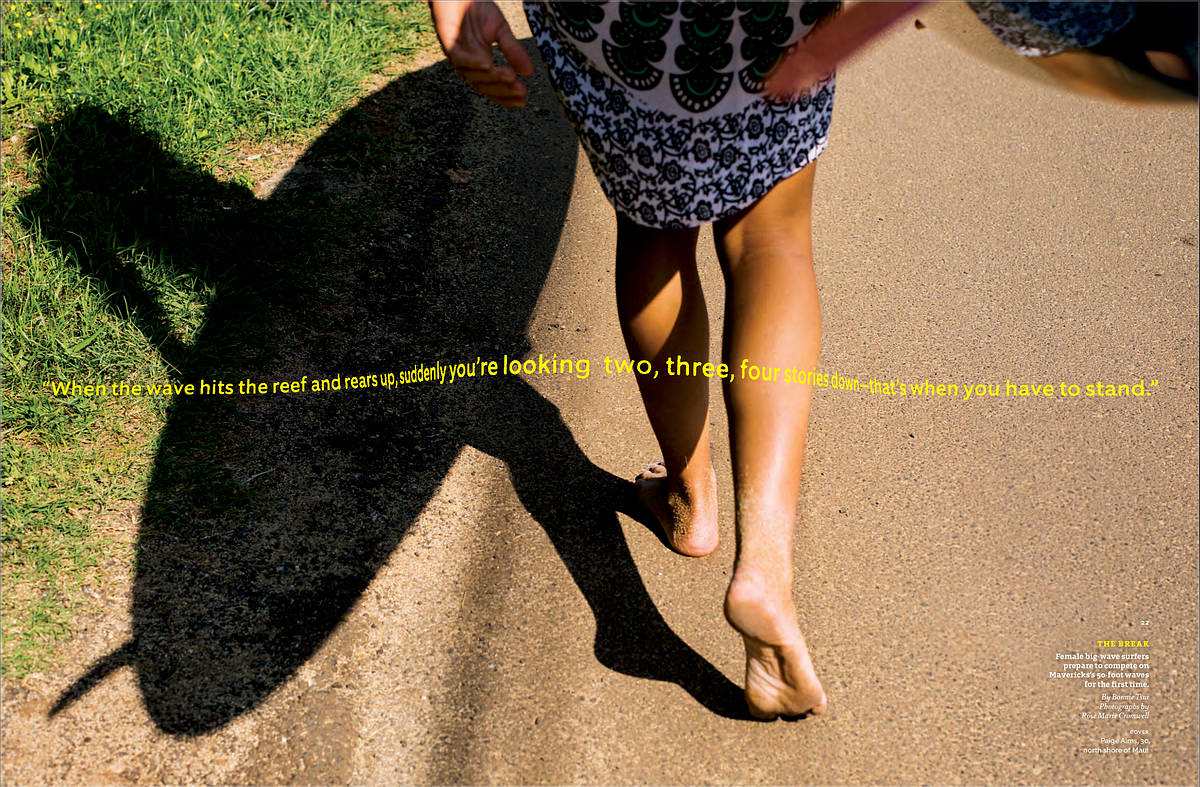

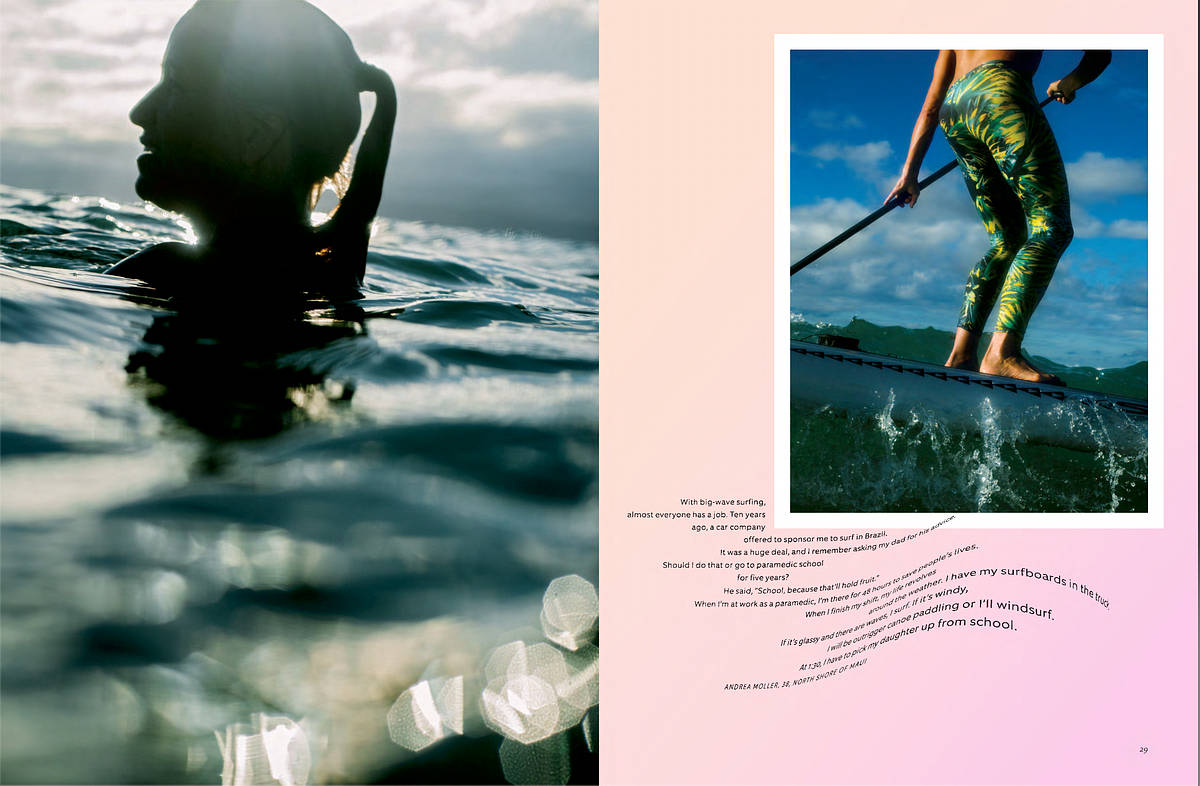

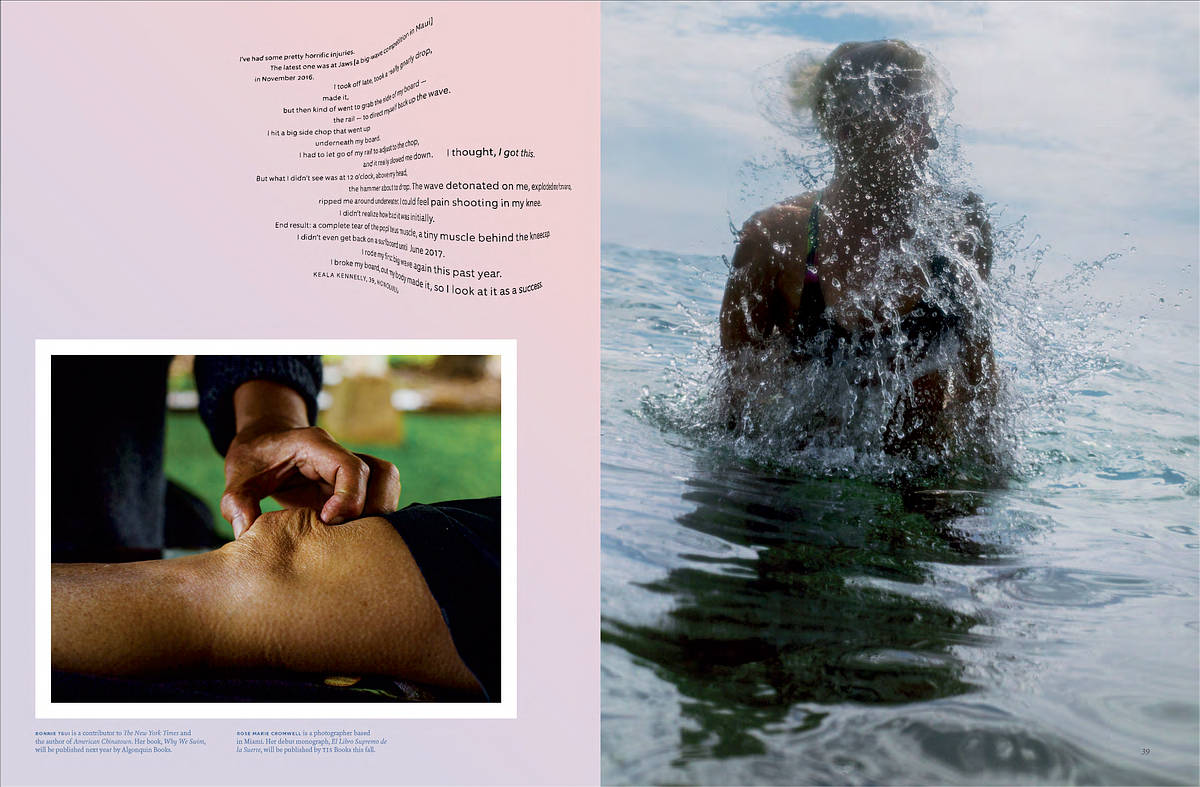

In 2016, Valenti and three fellow big-wave surfers — Paige Alms, Keala Kennelly, and Andrea Moller — helped establish a women’s division. But a big obstacle remains: Mavericks invitationals are as fickle as the wave itself. Over the past 19 years, the contest has been held just ten times. If at any given moment a big swell appears during big-wave season (likely from November through March), competitors from around the world are given 72 hours’ notice to make their way there. This year, nine women — six contestants and three alternates — stand to get that call.

.

Bonnie Tsui